One of the most unintuitive parts of photography (for me at least) is the fact that lower f-stops means greater aperture sizes. I have three main questions when it comes to lens apertures:

- Why are f-stops such weird numbers?

- Why do larger f-stops let in less light?

- Why do smaller f-stops require larger lenses?

Definitions

First, some photography terms. These definitions are given in a photography context, but they can often have slightly different meanings in different optical systems1. They’re also not universal but I’ll use them consistently here. I’m also not going to get into why wider apertures are more desirable in a lens, which normally comes down to better low-light performance and shallower depth of field. Shallower depth of field means more bokeh.

Depth of field as narrow as a fly…Taken with a 35mm prime @ f/2.6.

Camera lenses have an opening called a diaphragm at the back, controlling the amount of light that reaches the sensor. Aperture is the diameter of the diaphragm opening. Increasing the aperture, or opening the diaphragm more, allows more light to reach the camera’s sensor. The focal ratio, or f-number, is the ratio of a lens’ focal length to its aperture. The key equation is: 𝐴 = 𝑓∕𝑁 where 𝐴 is the lens aperture (in mm), 𝑓 is the lens focal length (in mm), and 𝑁 is the f-number.

Because aperture is the denominator of the focal ratio, increasing apertures mean lower f-numbers, and vice versa. This is why low f-numbers mean more light. F-numbers are even written in fraction form, essentially telling us that at f/2 the aperture is ½ the focal length 𝑓.

Denominators

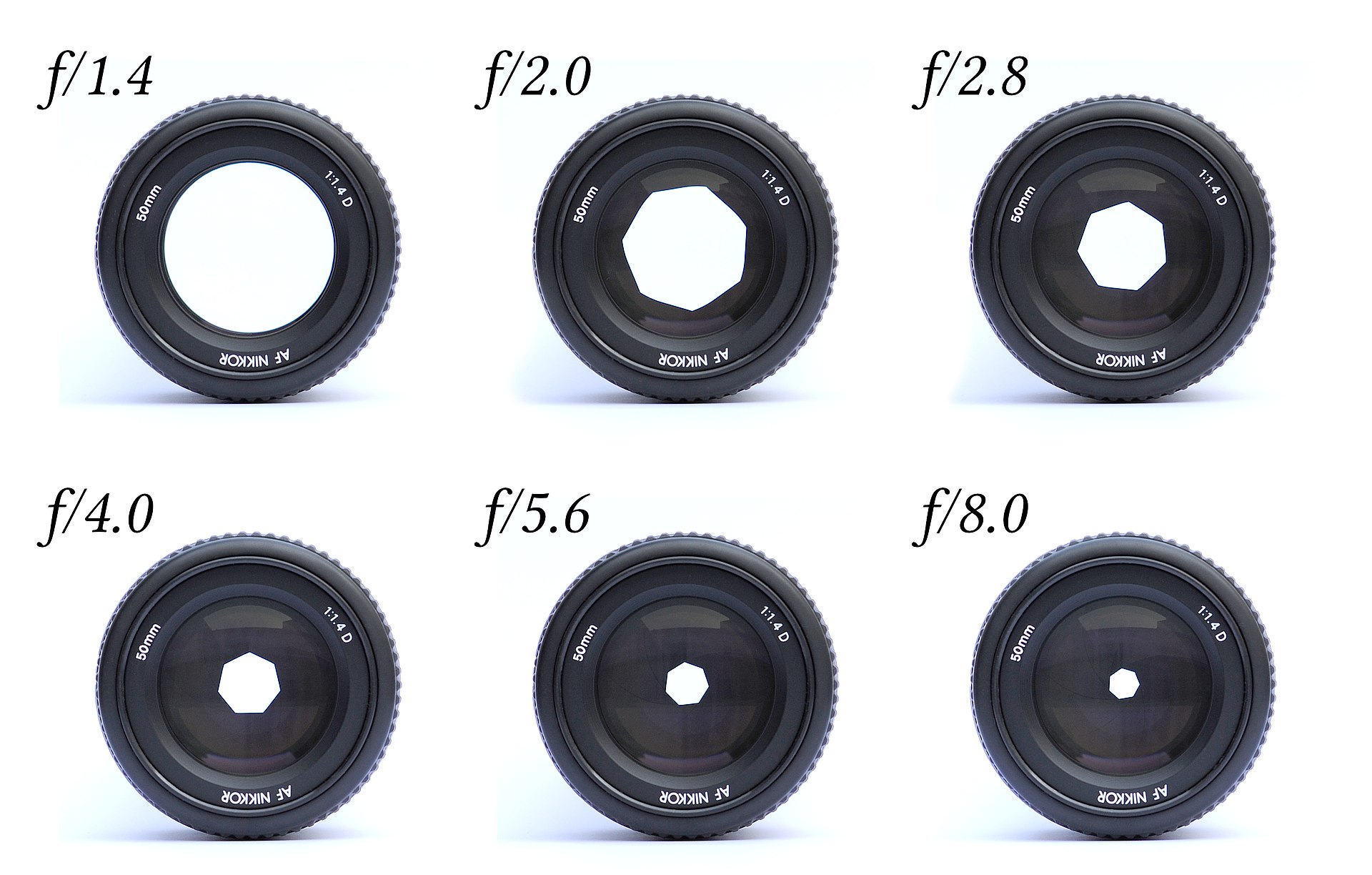

In theory, a lens diaphragm can be set to any f-number between 0 and infinity. In reality, lenses allow photographers to choose from a discrete set of f-numbers called f-stops. Common f-stops should be pretty familiar to someone with a passing knowledge of photography: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6…

The amount of light reaching the sensor is proportional to the area of the diaphragm, which means it’s proportional to the aperture, squared. To double the amount of light reaching the sensor, the aperture needs to increase by √2, which is about 1.4.

The f-numbers chosen for f-stops are the powers of √2. As a result, holding everything else equal, each f-stop doubles the amount of light reaching the sensor2. Each stop, in photography terms, allows twice as much light in a camera. So f/1.4 and f/2 are one stop apart (one power of √2: 1.4 is √2¹ and 2 is √2²), while f/2 and f/5.6 are 3 stops apart.

Diameters

Along with focal length, lenses are typically categorised by their minimum f-stop (i.e. their extent of their light-gathering and depth of field capabilities). This is for good reason: holding everything else equal, there’s a big increase in shape, size, and cost associated with lowering a lens’ minimum f-stop (increasing the maximum aperture).

For reference, compare two Fujifilm lenses above with the same focal length (50mm), but different minimum f-stops. The larger f/1.0 lens costs about 4x more than the f/2.0 lens and is nearly twice as long. Above f/2.0, they do exactly the same thing!

But now we know why: the diaphragm of the f/1.0 lens has to let in four times3 as much light as the f/2.0 lens. The glass at the base of the lens must have twice the diameter. Other glass elements inside the lens must also expand to compensate, increasing bulk and cost. This also explains why lenses with the same minimum f-number are more expensive at longer focal lengths: as the focal length increases, the aperture width must increase in proportion to maintain the same f-number.

Denouement

Ultimately the creativity in photography is governed by maths. The workings of lenses and cameras are abstracted away behind clean interfaces and automatic shooting modes (nothing wrong with shooting on auto), but it can still be useful to understand how parts of the camera work. Spending one second less thinking about which way to change the aperture setting can be the difference between capturing the right moment and missing out. Hopefully this post helps.

-

In non-photographic optical contexts, diaphragm and aperture can both mean the physical opening. In non-optical contexts, diaphragm can mean a thin muscle at the base of the chest. ↩

-

Formula for the area of a circle: A = π∙r². Increasing r by a factor of √2 causes A to double (√2² = 2). ↩

-

1 is √2⁰, while 2 is √2²: 2 stops (2 powers of √2) apart. Each stop is double the area, so 4 times total. ↩